The journey of a diamond from the mine to the consumer’s finger is a fascinating one. Before it becomes a permanent part of any diamond consortium, it starts, as you know, in a diamond mine where tonnes of the earth is sifted through to find the precious crystallized carbon deposits. However, most of the diamonds aren’t even gem-quality diamonds used for industrial purposes and industrial tools. Because of their hardness, they are tipped on saw blades and rotary saws to facilitate constructional purposes.

But the tiny percent that makes it to the gem industry go through a convoluted process. The gem-quality rough diamonds are first collected and put into packages. The diamond corporation in charge generally has a set number of clients called site holders in the industry, who are substantial companies. They have to meet precise criteria to be accepted into this exclusive club. Now, the site holders have to commit to a set dollar amount purchase every month, and they generally don’t have the ability to reject any of the items in that parcel.

These site holders, who are also members of larger diamond consortiums, either forward the content of these packages to other companies to manufacture them or manufacture them themselves. Manufacturing here indicates the process of taking a rough diamond and polishing and fashioning it into the shiny gem that you are used to seeing. A large part, around 40-50%, of the rough diamond is lost in this process, which means if they have a one-carat rough diamond, the end product is about 60% of a carat. This loss does not translate into a monetary loss because the lost rough diamond is factored into the finished product’s price.

There is a huge trade of rough diamonds within diamond consortiums as well. Rough diamonds are parceled and are brokered between companies to maximize returns on the rough diamonds if you do not intend to produce the actual diamond.

Once the gems reach their end form, they are sold through a network of dealers worldwide. You can have dealers sitting in diamond cities such as New York, Dallas, Chicago, Los Angeles here in the United States, or across the globe in Sydney, Mumbai, Tel Aviv, Antwerp, etc. These dealers purchase in bulk from their manufacturer suppliers, usually based on pre-defined terms. And they, in turn, sell to wholesalers or directly to retailers.

Now, some specific or unique diamonds are given to brokers in the city. The broker’s responsibility is to connect between the wholesale merchant and the dealer, or the retail merchant diamond and the dealer.

That’s generally the chain of events before the rough diamond reaches the end-user.

However, over the years, as in any industry, there is always an attempt to cut out the middle man. So, many retailers bypass wholesalers and dealers, create relationships with the manufacturers overseas, and purchase directly from them. In some situations, diamond manufacturers become jewelry manufacturers themselves and produce the end product to sell directly to retailers. They open up websites and sell them to consumers from there.

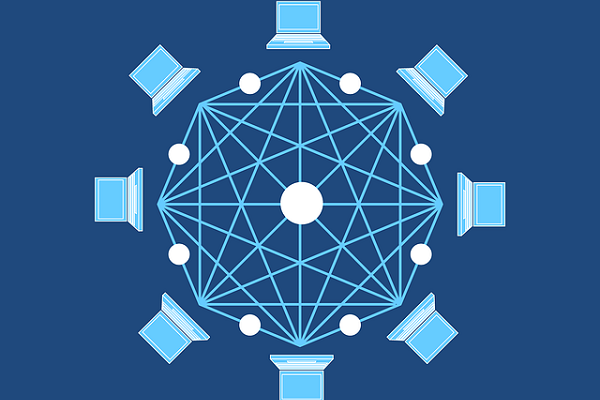

Evidently, it is challenging, if not impossible, in some cases, to keep a tab on the precious rocks as they move from one step of the supply chain to another, which often results in frauds, misplacements, and thefts. To curb this recurring problem, diamond consortiums like De Beers and Diamante incorporate blockchain technology to track registered diamond movement in real-time. A decentralized, immutable, digital ledger will add transparency and unparalleled security to the data cache, which is meant to file details of every transaction within the Diamante network to increase trust and accountability among participants across sectors in the industry. Such a system will also actively work toward reducing diamond-related crimes, the gem being the most preferred currency circulating in the underworld.

Source: Original